The Bank of England is expected to lower interest rates four times this year to stimulate a stagnant economy, according to a Reuters poll of economists. However, inflation risks remain on the

upside, raising the possibility that policymakers might take a less aggressive approach.

Interest rate futures currently indicate only two rate cuts this year. Meanwhile, turbulence in global bond markets reflects mounting inflation concerns, partly attributed to the protectionist economic policies of U.S. President-elect Donald Trump.

In the UK, inflation unexpectedly slowed last month, with core inflation—closely monitored by the Bank of England—declining even more significantly. This may provide room for further rate cuts, even as the U.S. Federal Reserve nears the end of its tightening cycle.

Despite futures suggesting only two 25 basis point cuts, 60% of the 63 economists polled between January 10 and 15 expect four cuts, bringing the Bank Rate down to 3.75%. This outlook has remained consistent over the past month. All 65 economists surveyed predict a quarter-point rate cut at the next BoE meeting on February 6.

While near-term consensus is strong, doubts persist about how many cuts the BoE will ultimately deliver. Recent cautious comments from policymakers have reinforced this uncertainty.

“With underlying inflation already elevated and survey-based inflation expectations rising, the BoE may become more cautious,” JP Morgan economists noted. “We anticipate a February rate cut, but the Bank may struggle to project confidence in further easing if inflation expectations keep climbing.”

In fact, 23 of the 25 economists responding to a supplementary question said inflation was more likely to exceed forecasts than fall short. Consumer price index (CPI) inflation is expected to average 2.5% this year and 2.1% in 2026.

The pound and UK government bonds have faced sharp sell-offs recently, mirroring trends in U.S. Treasuries and pushing the 10-year gilt yield to its highest level since 2008.

“The rise in yields is primarily driven by global factors,” explained Michael Saunders, senior advisor at Oxford Economics and former BoE policymaker. “However, domestic fiscal concerns could impose a risk premium on UK assets. In such a case, the Monetary Policy Committee might need to maintain higher rates to counter the inflationary effects of a weaker pound. That said, this is a risk scenario, not our baseline view.”

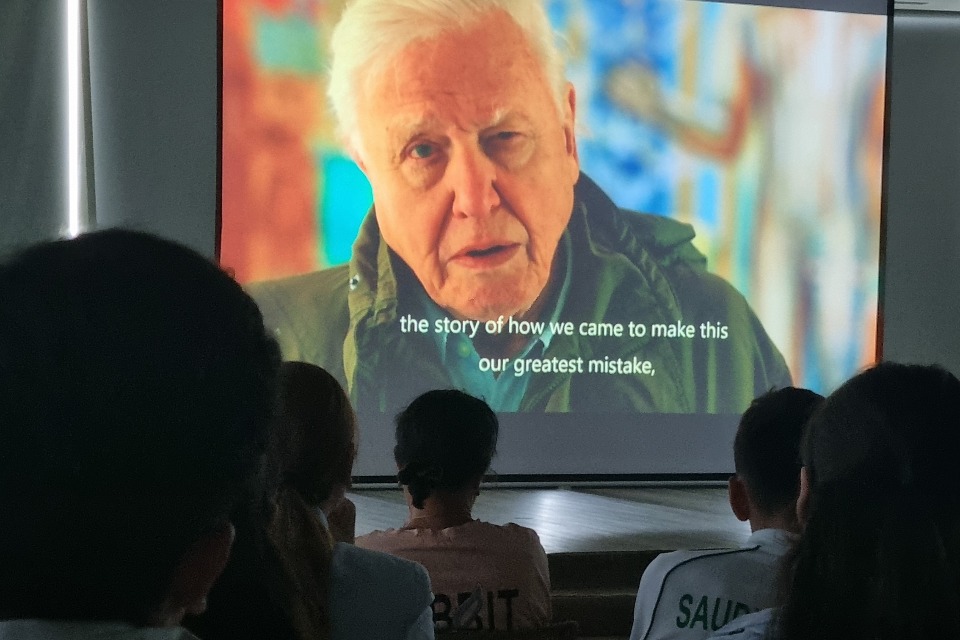

The UK economy grew minimally in the latter half of last year and is projected to expand by just 0.9% in 2024, with average growth forecasts of 1.3% for 2025 and 1.5% for 2026. Photo by Katie Chan, Wikimedia commons.